Houthis fighters raised various flags during a rally held in Sana’a,

Yemen in 2024 | Credits: Mohammed Huwais/Agence FrancePresse/Wall Street Journal.

Valentina Ramos

The America-Eurasia Center

The International Security Program

www.EurasiaCenter.org

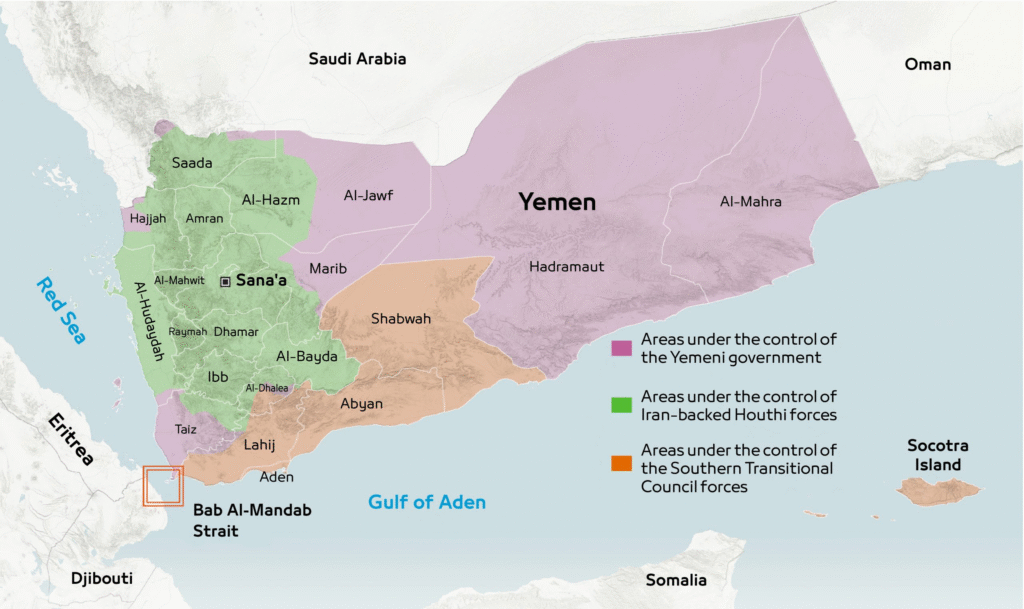

Map of Yemen separating the areas under control by different actors. | Credits: Trends Research & Advisory

Background

Since late 2023, Yemen’s Houthi movement has waged an intensified campaign against

vessels traversing the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, citing solidarity with Palestinians during the

Israel-Hamas War.1 Over 100 commercial and military ships, linked to Israel, the United States,

and the United Kingdom, have been struck using Iranian-supplied missiles and drones,

transforming the Bab al-Mandeb.2

The Bab al-Mandeb is a strategic strait between Yemen and the Horn of Africa, connecting

the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden. This strait accounts for about 10% of global trade3,

especially oil shipments. The drone and missile attacks in the strait have made the key trade

route dangerous and unstable, causing global shipping routes to be rerouted, raising costs and

slowing delivery, destabilizing one of the world’s most vital trade arteries.

Map of the Bab al-Mandeb strait. | Credits: InterlogUSA

In response, the United States and the United Kingdom have deployed naval and air forces

to begin operations in early 2024 to secure the shipping lanes under. Operation Prosperity Guardian

to secure maritime routes and deter the Houthis aggression.4 These efforts later escalated to

Operation Rough Rider5, lasting from March to May 2025, during which U.S. airstrikes targeted

Houthi launch sites, drone storage, and radar infrastructure across western Yemen.

The conflict reached a pivotal point on May 4, 2025, when a Houthi missile strike landed

near Israel’s Ben Gurion Airport.6 The next day, Israel launched its first-ever naval strike on the

Houthi-controlled port city of Hodeida, signaling a geographic and tactical escalation in the

conflict.7 The Houthis’ battlefield expansion is the product of a deliberate proxy architecture,

anchored by Iran’s evolving regional doctrine.

The Houthi-Iran Axis

Iran is the primary state backer of the Houthi movement, and the only major country to

maintain a recognized political relationship with the Houthi leadership in Sana’a. According to the

Council on Foreign Relations, Tehran has supplied the Houthis with precision-guided munitions,

drones, anti-ship missiles, and training support through the Quds Force of the Islamic

Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).8 This partnership, believed to have begun as early as 2009,

has since evolved into a key pillar of Iran’s regional strategy. The Sana’a Center for Strategic

Studies suggest that Iran’s support has steadily expanded from ideological sympathy to active

logistical, financial, and intelligence aid in recent years.9

However, the nature of the Houthi-Iran relationship remains a topic of debate. While Tehran

provides extensive material and ideological backing, some scholars warn against oversimplifying

the Houthis as a mere proxy. A Brookings Institution article argues that the group retains significant

local agency and domestic roots, and that its alignment with Iran is more strategic than

subordinate.10

That said, Iran still benefits immensely from the Houthis’ campaign. The actions of the

Houthis divert Western military attention, pressures Israel from a southern front, and disrupts

maritime flows—all without risking direct confrontation. As a result, Iran’s use of the Houthis

exemplifies 21st-century proxy warfare, where influence and disruption are achieved without

conventional battlefield engagement.11 The Houthis’ campaign, backed by Tehran, has far-reaching

implications that extend beyond Yemen, reshaping the regional balance of power.

Geopolitical Shifts

Far from being a localized insurgency, the Red Sea conflict has set off tectonic shifts in how

regional and global powers engage with maritime security, by escalating Houthi attacks and the

widening scope of proxy warfare. Following U.S. and U.K. strikes under Operation Rough Rider

and Israel’s unprecedented naval strike on Hodeida in June, the Red Sea ceased to be a peripheral

front—it became central to the global contest over chokepoint control and maritime security.12

Smoke rising up after an explosion in Tehran, Iran. | Credits: Vahid Salemi/AP/ CBS

In response, Iran adopted a measured but firm course. Following Israel’s June 10 strike on

Hodeida, Tehran vowed a “harsh and decisive” response but refrained from immediate escalation.13

On June 13, it launched around 100–200 ballistic missiles and over 100 drones toward Israel— its

first direct retaliation in this theatre.14 Iran also placed proxies like Hezbollah and the Houthis on

alert while positioning its actions within a “resistance” narrative, balancing proxy pressure and

diplomacy. This hybrid posture showcases Tehran’s effort to flex power without triggering full-scale war.

Meanwhile, Gulf powers altered course. Saudi Arabia doubled down on its 2023

rapprochement with Iran, seeking distance from Houthi retaliation and U.S.-led operations.15 The

UAE scaled back naval patrols, refocusing on internal security and commercial port resilience.

Egypt, caught between economic dependence on the Suez Canal and regional chaos, sought greater

Chinese maritime investment and security guarantees.16 These shifts reveal a broader pattern:

regional powers are adapting to a new reality where U.S. security guarantees are no longer taken

for granted.

2025 also saw China expand port surveillance and escort missions near Djibouti, quietly

asserting a non-Western maritime presence. These shifts reflect a growing strategic decoupling

from Western security frameworks, as the Red Sea becomes a testing ground for 21st-century

asymmetric naval power and post-American regional order.17

U.S. Involvement

In May 2025, President Trump brokered a fragile ceasefire with the Houthis through Omani

mediation, ending the near-constant strikes of Operation Rough Rider, which had delivered over

1,000 airstrikes aimed at protecting Red Sea shipping lanes and supporting Israel’s deterrence

posture.18 The agreement halted U.S. bombing and reduced piracy risks—but deliberately excluded

Israeli-linked Houthi strikes, allowing the Houthis to continue targeting Israeli vessels and

territory.19 This gave the U.S. a diplomatic win in safeguarding maritime commerce, yet undercut

broader regional stability

The ceasefire also served as a strategic messaging tool: Washington demonstrated it could

project power and then pause sanctions to encourage de-escalation—reinforcing its role as regional

security architect. However, when Israel launched its naval strike on Hodeida in June, triggering

Iran’s missile retaliation, the ceasefire’s limitations became apparent. It revealed that U.S. influence

alone could not contain escalation between other strong actors, such as Israel and Iran, nor manage

the complex web of proxy networks.20

Looking ahead, the ceasefire outlined the future of U.S. engagement as conditional and

interdependent. American military backup now depends on alliance cohesion, diplomatic

coordination, and balanced messaging that avoids drawing the U.S. into direct conflict.21 The U.S.

has positioned itself more as an architect of crisis containment than a unilateral enforcer—a shift

with lasting implications. While this indirect posture conserves American influence and reduces

direct risks, it also means unresolved tensions remain poised to reignite, revealing both the

strengths and limits of U.S. power in proxy war environments.

Conclusion

The intensified Houthi campaign in the Red Sea, backed by Iran, has fundamentally

reshaped regional geopolitics and global maritime security by exploiting strategic chokepoints and

leveraging proxy warfare. The United States’ calibrated military and diplomatic responses under

the Trump administration reflect a delicate balance between projecting power and avoiding direct

entanglement, revealing both the strengths and limits of American influence in a multipolar,

contested landscape. As proxy wars persist and the capabilities of militant groups continue to

advance, this evolving conflict underscores a critical warning: without sustained multilateral

diplomacy and coordinated security efforts, the potential for wider regional instability and

prolonged violence remains a pressing and dangerous reality.

- Kalin, Stephen, and Shelby Holliday. 2025. “How the Houthis Rattled the U.S. Navy—and Transformed Maritime War.” WSJ. The Wall Street Journal. June 5, 2025. https://www.wsj.com/world/middle-east/navy-houthis-maritime-war5517a127?utm_source=chatgpt.com. ↩︎

- Guardian staff reporter. 2025. “Israeli Navy Attacks Yemeni Port City of Hodeidah for First Time in Conflict.” The Guardian. The Guardian. June 10, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/10/israeli-navy-attacks-yemeni-port-city-of-hodeidah. ↩︎

- “The Geopolitical Importance of Bab El-Mandeb Strait: A Strategic Gateway to Global Trade – MEPEI.” n.d. https://mepei.com/the-geopolitical-importance-of-bab-el-mandeb-strait-a-strategic-gateway-to-global-trade/. ↩︎

- “The Houthis, Operation Prosperity Guardian, and Asymmetric Threats to Global Commerce – Center for Maritime Strategy.” 2024. Center for Maritime Strategy – Center for Maritime Strategy. July 18, 2024. https://centerformaritimestrategy.org/publications/thehouthis-operation-prosperity-guardian-and-asymmetric-threats-to-global-commerce/). ↩︎

- Schmitt, Eric, Edward Wong, and John Ismay. 2025. “U.S. Strikes in Yemen Burning through Munitions with Limited Success.” The New York Times, April 4, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/04/us/politics/us-strikes-yemen-houthis.html. ↩︎

- Farnaz Fassihi, “Houthi Missile Strikes Near Tel Aviv Airport — Israel Says,” The New York Times, May 4, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/04/world/middleeast/houthi-missile-tel-aviv-israel.html. ↩︎

- “Israeli Navy Attacks Rebel-Held Yemeni Port City.” AP News. June 10, 2025.

https://apnews.com/article/mideast-wars-yemen-israel-hodeida-attack-7857d9fc0e5293cf6f2573493281bdf7. ↩︎ - Kali Robinson, “Iran’s Support of the Houthis: What to Know,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 1, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/irans-support-houthis-what-know. ↩︎

- “Saudi-Houthi Talks Sow Cracks in Coalition – the Yemen Review, January and February 2023,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, March 13, 2023, https://sanaacenter.org/the-yemen-review/jan-feb-2023. ↩︎

- Allison Minor, “The Danger of Calling the Houthis an Iranian Proxy,” Brookings, September 3, 2024,

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-danger-of-calling-the-houthis-an-iranian-proxy/. ↩︎ - Fatimo Abo Alasar and Behnam Ben Taleblu, “Iran’s Shadow Looms Large over the Houthi Ceasefire,” Atlantic Council, May 21, 2025, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/iran-houthi-strategy/. ↩︎

- Jon Gambrell, “Israeli Navy Attacks Rebel-Held Yemeni Port City,” AP News, June 10, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/mideastwars-yemen-israel-hodeida-attack-7857d9fc0e5293cf6f2573493281bdf7. ↩︎

- “Iran Strikes Back at Israel with Missiles over Jerusalem, Tel Aviv,” Reuters, June 13, 2025,

https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/israel-strikes-back-iran-says-strikes-iran-amid-nuclear-tensions-2025-06-13/. ↩︎ - Joe Walsh, Haley Ott, Tucker Reals, and Kerry Breen, “Iran Launches Missiles at Israel, and Some Hit Tel Aviv, as Israel Attacks Iranian Nuclear Sites and Commanders,” CBS News, June 14, 2025, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/iran-israel-drone-attackretaliation-strikes-on-nuclear-sites-and-commanders/. ↩︎

- Faozi Al-Goidi and Tanner Manley, “Saudi-Iran Rapprochement Unlikely to Bring Lasting Peace to Yemen,” Middle East Council on Global Affairs, April 13, 2023, https://mecouncil.org/blog_posts/saudi-iran-rapprochement-unlikely-to-bring-lasting-peace-toyemen/. ↩︎

- Nadia Helmy, “How the Belt and Road Initiative is Transforming Egypt and the Suez Canal Economic Zone,” Modern Diplomacy, March 28, 2025, https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2025/03/28/how-the-belt-and-road-initiative-is-transforming-egypt-and-the-suez-canaleconomic-zone/#:~:text=Egypt%20is%20one%20of%20China

s%20pivotal%20partners,most%20important%20maritime%20corridors%20for%20global%20trade. ↩︎ - Congressional Research Service, “China’s Engagement in Djibouti,” IF11304, March 28, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crsproduct/IF11304#:~:text=China%20and%20Djibouti%20announced%20in,to%20the%20U.S.%2DDjibouti%20relationship. ↩︎

- Michael Knights, “What the End of the Houthi Campaign Means for U.S. Power,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, May 19, 2025, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/what-end-houthi-campaign-means-us-power. ↩︎

- Idrees Ali and Phil Stewart, “U.S. Bombing Dents but Doesn’t Destroy Houthi Threat in Yemen,” Reuters, May 7, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-bombing-dents-doesnt-destroy-houthi-threat-yemen-2025-05-07/. ↩︎

- Mohamad Bazzi, “Netanyahu Outplayed Trump on Iran. Now the US Risks Being Mired in Another War,” The Guardian, June 14, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/jun/14/netanyahu-trump-iran-israel-war-risk ↩︎

- Andrew Davidson, “The US Shifts Course in the Red Sea Standoff,” Geopolitical Futures, May 19, 2025,

https://geopoliticalfutures.com/the-us-shifts-course-in-the-red-sea-standoff/. ↩︎